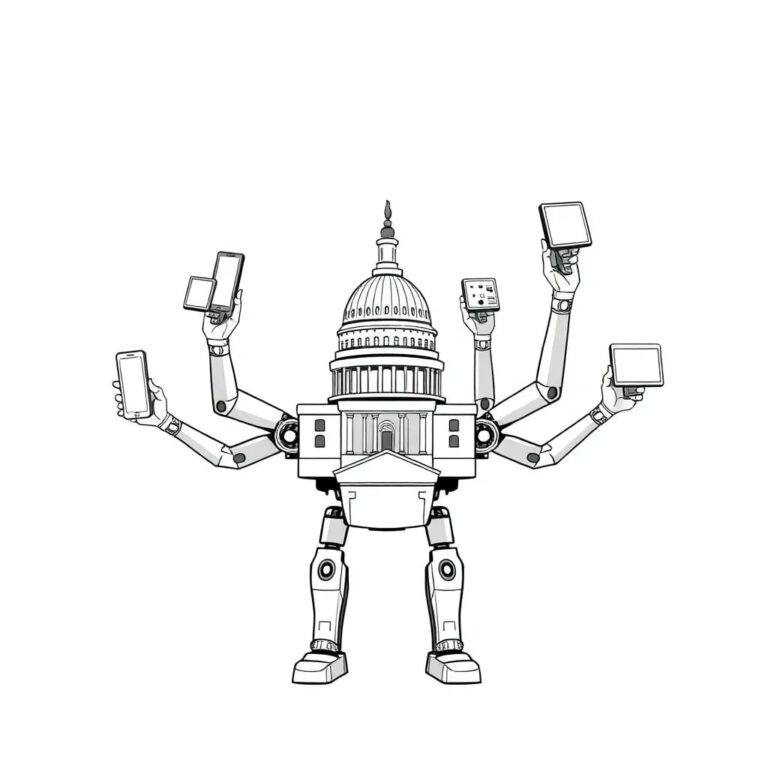

Congress Should Lead on AI Policy, Not the States

The temptation to “do something” on artificial intelligence will grow as the midterm elections draw near and the media continues to focus on fears about anecdotal AI harms. In particular, state lawmakers will continue to pursue many AI-related initiatives in 2026.

Over 1,200 AI-related laws were floated in 2025, and more than 180 passed. While some of these regulations may be well-intentioned, and a few even necessary, it is likely many will run afoul of constitutional principles.

Constitutional Concerns

These constitutional flaws cannot be dismissed by analogizing AI to earlier technologies in which states played a significant legislative role. Much more so than the technologies that characterized the agrarian and industrial ages, AI development and deployment implicates interstate commerce and speech considerations, and accordingly, may in some cases violate the dormant commerce clause or the First Amendment.

AI Is Not Pencils or Pork Bellies

State AI regulations have a different nexus with interstate commerce than other state laws. These distinctions have legal consequences. In its 2023 ruling in National Pork Producers Council v. Ross, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld a California law that prevented the sale of pork that fell short of the state’s confinement standards.

A key factor in that decision was that out-of-state producers have myriad ways to alter their operations to minimize the disruptive effect of the law. In contrast, algorithmic and computational commerce often mandates just that. The underlying technology is highly interconnected, intangible, and instantaneous. From how AI is trained to how it is deployed by end users, a nationwide digital infrastructure is called on by many AI laws.

The modern digital economy and online speech thrive in the U.S. because, generally speaking, the nation has not treated digital data flows as uniquely geographic, place-dependent events. Bipartisan policies established in the mid-1990s helped ensure that did not happen.

Potential Pitfalls of State Regulation

An “AI Articles of Confederation” approach would reverse the past 30 years of digital technology policy and undermine the nation’s efforts to create a coherent national AI policy framework. Such a regulatory model will be particularly problematic for smaller innovators without the legal compliance teams needed to deal with the mountains of confusing and costly compliance requirements.

Moreover, the fact that AI is also an information technology means that there are often important speech-related considerations at stake that necessitate greater scrutiny and protection. For this reason, state efforts to legislate AI policy may be problematic not only because they create a confusing patchwork but also because some laws impose speech restrictions and obligations that violate the First Amendment.

The Role of Congress

When Congress chooses to remain silent on AI governance matters, a balkanized regulatory scenario could be where the nation is heading. An avalanche of parochial AI regulation looms as state and local governments appear ready to push the horizons of AI regulation further.

Congress must assert itself and create a national policy framework that limits the potential emergence of a fragmented regulatory environment. For instance, New York and California have both recently passed major bills addressing frontier AI systems, which should not dictate national standards for AI labs located outside their borders.

Conclusion

States will likely continue to have some leeway to legislate around novel algorithmic issues as they develop, but it is entirely reasonable for the federal government to have a say in how that process works to avoid definitional confusion and needless red tape that would deter interstate innovation and competition.

While both states and the federal government have roles to play in governing AI, getting this balance of powers and responsibilities right is not easy. Congress must not abdicate its responsibility and cede control over this interstate market to state and local officials.